10 Years of DIVIDE & EXIT

WHO CARES ABOUT ROCKSTARS ANYMORE?

Words: Kieran Poole

Noel Gallagher once sneered, “There’ll never be another Bowie because of cunts like Sleaford Mods.” So looking back, Divide and Exit seemed fitting for the title of Nottingham duo Sleaford Mods’ second outing.

It’s 2013 again, or maybe it’s not. Time blurs when you’ve got half a memory and twice the bad habits. Back then, a monotony of 6 til 6 abbatior factory hell, Lee Scratch Perry’s Super Ape on repeat, and casual shoplifting made the schedule.

A decade later, I still listen to Super Ape but have since moved on to self-serve scanners.

It was the mid-term Tory hangover; Cameron’s days were numbered, UKIP had started opening registration offices like some weirdo Vietnam sign-up depot, and zero-hour agency-ruled contracts flourished.

Austerity was now more than a buzzword—as if it were some kind of noble sacrifice and not a slow bleed of anything worthwhile. Thinking about it, that moment never ended. It’s still unfolding, like a slow-motion car crash that we’re all somehow still part of.

The early 2010s was a time when the last fumes of indie lingered, like the smell of stale lager in a festival tent. The winkle pickers and the sunglasses on stage brigade were still present - All desperately clawing at relevance, like moths to the flickering bulb of the NME’s dying machine.

Third-wave ‘radar’ bands copying first-wave ‘radar’ bands, who themselves were barely treading water.

A closed loop of unmitigated shite, clinging to the coattails of other shite, all sinking together into the quicksand of cultural irrelevance.

The genre clung to existence by siphoning any glimmers of authenticity from the genuine bands, only to pump out a slurry of generic riffs, knowing winks and a desperate attempt to obscure the fact that they had absolutely nothing new to say.

Every release was a limp photocopy of a photocopy, each subsequent band sounding slightly more like a dial-up modem trying to cover the first Strokes album, now in loafers - We now know it as late-stage ‘landfill indie’ - But I think it was worse than that.

It did, however, give birth to the likes of Factory Floor’s speed-fuelled electronic debut and Fat White Family’s Mark E. Smith-inspired dark rockabilly—I'm not saying as if we were starved of an antidote to the overblown fodder from Kasabian’s weak carry-on, Two Door Cinema Club, or whatever overcooked turd the not-quite-dead, but getting there ‘Fly Magazine’ had thrust upon us - Someone needed to cut out the middlemen and throw the guitar pedals in the river for a bit.

I dived into Sleaford Mods via Austerity Dogs (their first “proper” album), a year after its release. At the time, I was probably still convinced the idea that “real punk” came in the form of Mark Perry’s ‘Sniffin Glue' zines or one of those 50,000 Don Letts documentaries on BBC4, endlessly regurgitating, “Those were the punk rock days.” Yes, I watched them all. Yes, I nodded along, like a well-trained seal.

Austerity Dogs felt both entirely fresh and bizarrely retro—a kind of 2013 electronic punk that somehow bypassed all the “artistic” rubbish. It wasn’t trying to be edgy or “experimental”, nor was it interested in the critics’ constant labels of John Cooper Clarke, Suicide or any other supposed ‘boundary-pushing art jaunts’ that had torn the rule book up and started from ground zero. Looking back, It probably had more in common with The Exploited and English Dogs than any of those.

No one seemed to be doing what Sleaford Mods were back then. It was still punk, but just without the poser bullshit. It made 1977’s yesteryears look like well-polished museum pieces.

Divide And Exit arrived a year and a bit after Austerity Dogs.

It built on the foundations and rattled it around the back alleys of your brain a bit longer to pry open all those unsavoury details you’d rather leave untouched.

This was Sleaford Mods at their “most punk, class-conscious, and urgent”.

As with all of their output, Jason Williamson’s lyrics were undoubtedly the star attraction to Divide and Exit. Sprawling verses of character assassinations, the boredom of casual drug use, and the banality of it all are the sound of a thousand broken conversations happening at once.

I could list all the lyrical gems willingly, but there really are just too many great ones to choose from.

Do the work yourself. Listen to the record, and you'll hear lines like, “I won’t talk to nice people if they look rich, I know it’s not on, mate, I’m such a fucking bitch!”

Williamson seemed to hold a mirror up at himself first, then turned it over to the audience for more grim reflection.

Then there’s Andrew Fearn, the other half of Sleaford Mods: A man of few words, presenting a masterclass in minimalism. Consisting largely of rough drum loops and low-end bass rumbles, they jolt each song further along and provide the perfect backdrop for Williamson’s lyrics. But this isn’t some krautrock for the punk scene; these are strange spiralling choruses floating atop a beat that consistently slaps you awake.

Tracks like "Tied Up in Nottz" and "Tweet, Tweet, Tweet" are reminders that you don't need layers of polish to achieve an intense atmosphere with very little.

"Air Conditioning" and "Liveable Shit" still hit hard today. Incredible, really. I mean, the subject matter hasn't aged a day. It's as fresh as the stagnant, recycled air still gliding in a world that insists on battling the same tedious issues -“Big car, Small life”, or who left the toilet door open because it fucking stinks!

Did I say there was humour?

LIVEABLE SHIT, YOU PUT UP WITH IT.You can easily find yourself diving into new territory with each listen, navigating your way through its murky waters with a new appreciation for every shitty pub in town where the air is thick with stale ambition and half-spoilt fame seekers.

Around this time, it seemed crazy that I had to argue the significance of Divide and Exit to people (you know, before “The Fame” and 6 Music heads joined in) who live in the eternal twilight of the Oasis/Lambretta universe.

“Where’s the fuckin’ guitars?” they whined, like some stunted Peter Pans who never realised the Wonderwall fell down years ago. “Just them two and a laptop, then, is it?”

As if that wasn’t exactly the point—Less was so much more in that landscape when you stripped away the bullshit.

Sleaford Mods proved that in spades.

Now a decade on and still as relevant, Divide and Exit stands as an unyielding monument to the disregard of overproduction and hours of staring at a pedal board.

It is a time capsule of disillusionment that hasn’t faded and a reflection of Britain at its most honest—Etched with corners of beauty, humility, and insecurity, pulling at the already half-battered sleeves that entangle you in.

“Sir Paul, you can find b-inspiration in everything.

The recyclable black bins bags of dog shit Angels sing.”

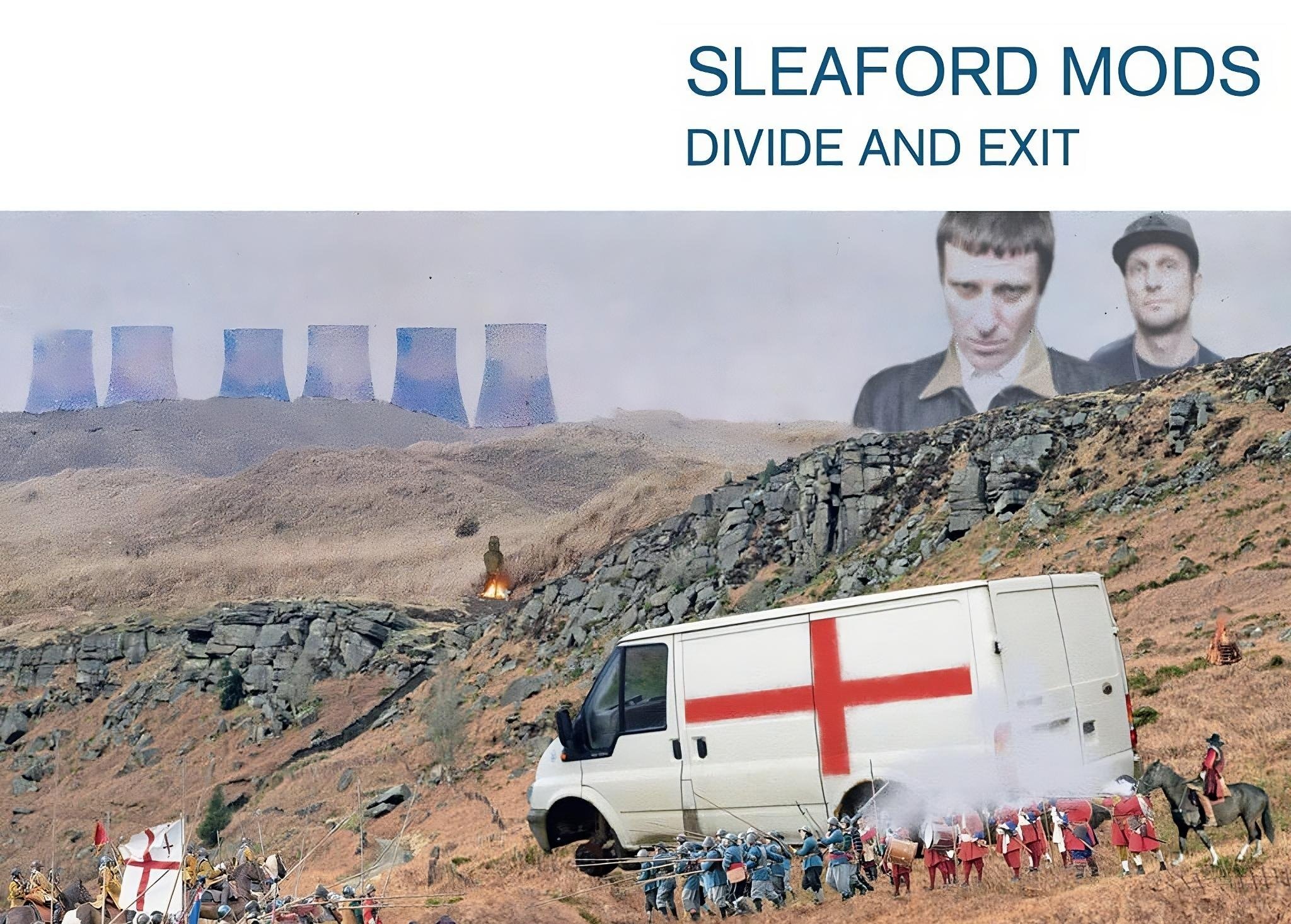

Divide and Exit: 10th Anniversary Edition is out now, accompanied by updated artwork by Cold War Steve.

But if you’re only getting around to listening now,

where have you been?